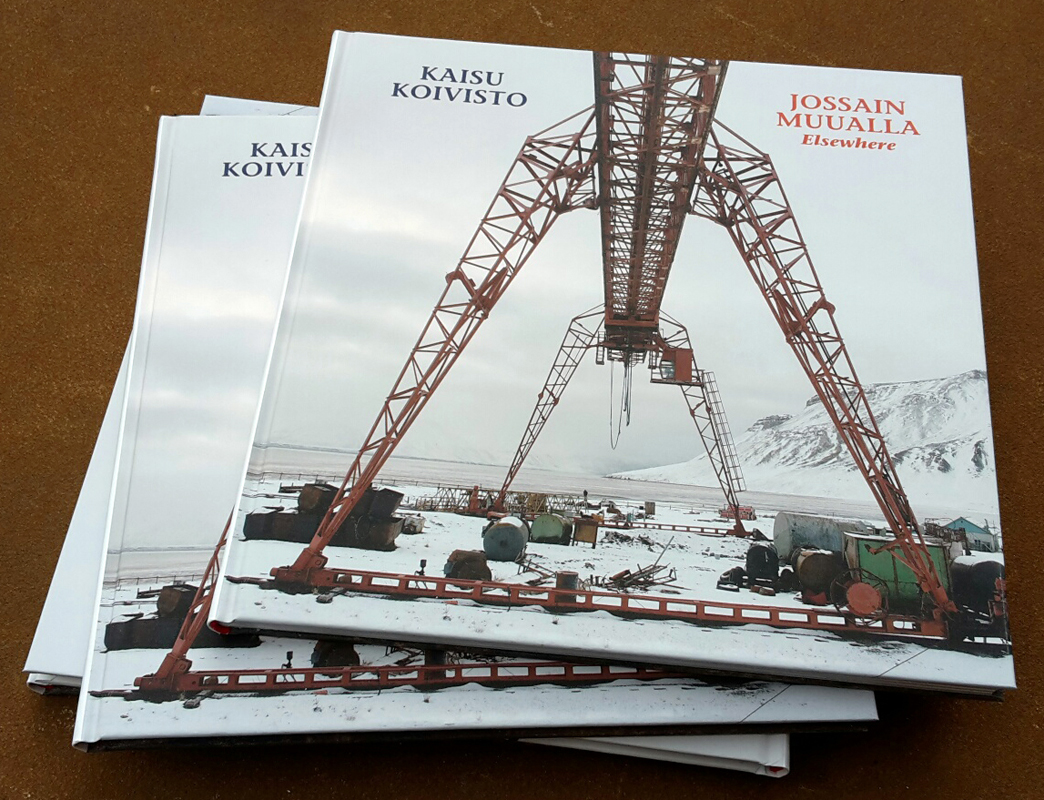

Landscapes from Somewhere Else

by Kaisu Koivisto.

Published in Kaisu Koivisto’s monography Elsewhere (Parvs publishing, Helsinki 2016)

The people have left, taking with them things and materials that are valuable and useful. A sentimental landscape painted on a concrete wall remains, flaking, cracking, peeling and decomposing. A picture of nature turning into nature.

For the past fifteen years or so, I have addressed notions of landscape, the environment and nature with the means of visual art. My themes and motifs are at the interfaces of history, ecology, technology, tourism and aesthetics. My works are created at the intersection of historical, personal and poetic elements associated with environments of various kinds.

I consciously seek out places that I assume to be significant for me and will serve the purposes of making art, seeking and finding. I photograph cultural landscapes, the culture of landscape. Brutally transformed areas where nature has first been erased and the soil has been prepared for military or industrial use. No conservation statutes or rulings of any kind apply to them. I photograph and draw above all at bases left behind by the Soviet army in former areas of the Soviet Union or within its sphere of influence, for example in the Baltic countries, Belarus and the former East Germany. Abandoned military areas are the remains of occupation by an invading power, relicts of a colonialism whose traces are often preferably forgotten or cleared out of sight.

My sculptures and installations combining steel and natural materials are comments on the way in which we view and use our surroundings: objects and the built environment, raw materials, animals and creatures. I consider what objects mean and why. These works have to do with a physical connection with the environment, matter, objects and their production. My photographic and video works, on the other hand, offer a means to perceive processes associated with time and history.

The environment in which I work is of great influence on the starting points, motifs and techniques of my artworks. I observe details around me, ones that I love: houses, structures, birds, roads, forests, parks and paths. I look at a mural by an anonymous artist on a wall in an abandoned military area. In that allusively and indirectly painted landscape I recognise the desire to depict something essential and important.

Colossal concrete structures that are no longer needed are gradually disintegrating into sand castles. Gravity is pulling the roofs down. For vegetation, the direction of growth is up towards the light. The relentless tenacity of small shoots to strike root anywhere, the roots pointing down to the water of life. Stunningly green moss. Owls, deer, cuckoos. Hangars for nuclear warheads, plastic waste, broken beer bottles, machine parts, gas masks, stands for theodolites.

Driving through endless stretches of forest, leafing through maps. I browse notes in my work journal and maps that I have drawn of the places where I am headed. Area. Base. Zone. There are things that make one nervous when going to abandoned military areas. Will there be guards and how can you avoid them? Will you be met by an owner who doesn’t approve of trespassers? My Russian skills are poor. How can I explain why we have driven to the back of beyond to photograph dilapidated buildings? The car is parked in a way that permits a quick exit

I am alert, observing everything around me. I stop to look, listen and smell. I am totally present in a way that you do not have to be elsewhere, and I might not even be able to do so elsewhere. I feel alive with every cell in my body. We move systematically from one building to another. Glass shards crackle under my safety footwear. I feel the flow of air on my face from window openings. There can be surprises anywhere, so every nook and cranny has to be checked. I proceed with curiosity, avoiding holes in the floor. I check the roof every now and then, thinking whether it is all right, whether it will remain intact. I photograph continuously, draw and take notes. I know from experience what kitchen and canteen buildings look like. They often contain what I am looking for, murals and landscape wallpaper.

Who made these fascinating landscapes? According to my information, people who displayed skills in the visual arts were ordered to make sculptures, reliefs and paintings for military bases.

The imagery of propaganda and its slogans boast of the superiority of the Soviet Union and its army, in military matters, sports and industry. The artworks at the bases were often made with few tools and materials. At the same time, materials that were available – concrete, bricks, steel, pebbles and wall paint – were ingeniously applied. It can be concluded from the locations of the propaganda works that they were important. The same visual motifs reoccur: diagrammatic maps of the victorious Great Patriotic War, depictions of branches of the armed services, the mechanised progress of industry, and leading figures and personages of the Soviet Union. Their plain visual language is undeniable. By contrast, leisure facilities and canteens contain pictures of birch forests, lakes, stormy seas and fields. Something to embellish harsh everyday conditions for a moment: landscapes of homesickness. I gave my series of photographs on this theme the title Landscapes of Longing.

Nature excursions on roads of concrete slabs. Observations of the tips and landfills of Cold War-era buildings constitute the archaeology of the recent past. These landscapes now reclaimed by forest were once centres of high technology. Even the latest technology will fall silent if it is not maintained.

My interest in the remains of the brave new world began from a closer look at recent history. My initial perplexity has changed over time to systematic field trips, photography and drawing. The passion to know and see more. When you do something sufficiently long and thoroughly enough it becomes a significant area of one’s life. The dilapidated vistas opening up in the outlying regions of Eastern Europe have become a part of my work and life. Spring sunshine and a building carelessly made of light-coloured bricks arouse a longing to get to these places that attract and repel at the same time.

Moving about and working in the wastelands of the post-industrial era always involve multiple factors of uncertainty and things that cannot be anticipated in advance. I do not know what remains of a site, if there is access to it or whether one can work there – not to mention the results of the trip. The excursion to the unknown is like the making of art: reaching out to something that is still emerging but will gradually achieve content and form. It is always the right moment to photograph. There can be no waiting, for before long these places will no longer exist.

The painted landscapes bring the outdoors inside and lead the gaze somewhere else. A soulscape. A mindscape. A cultural landscape. Interestingly, depictions of nature have less often been deliberately destroyed, for example by scratching or with spray paint, while propaganda imagery has been an excellent platform for expressing opinions about the former occupying power.

I consider the paired concepts of the external and internal world. Exterior and interior space. An abandoned building without doors, windows or furniture, with its birds’ nests and decaying wooden floors is like a fenestrated angular cave with a painting in its bowels. I see the crumbling and fallen building material from around the paintings as pieces of branches, mosses and stones framing the works. The structures and the images hidden deep within them begin to grow a new life of changes at their own pace with the flame of the unstoppable energy of the forces of nature.

A peeling awkwardly painted landscape mural is as moving as a hit tune belted out with feeling in a karaoke bar. The eternal desire to look at a landscape, make a picture of it, and to recognise something touching in it. This is the simultaneous feeling of familiarity and strangeness that I experience on my visits to these sites.

Kaisu Koivisto

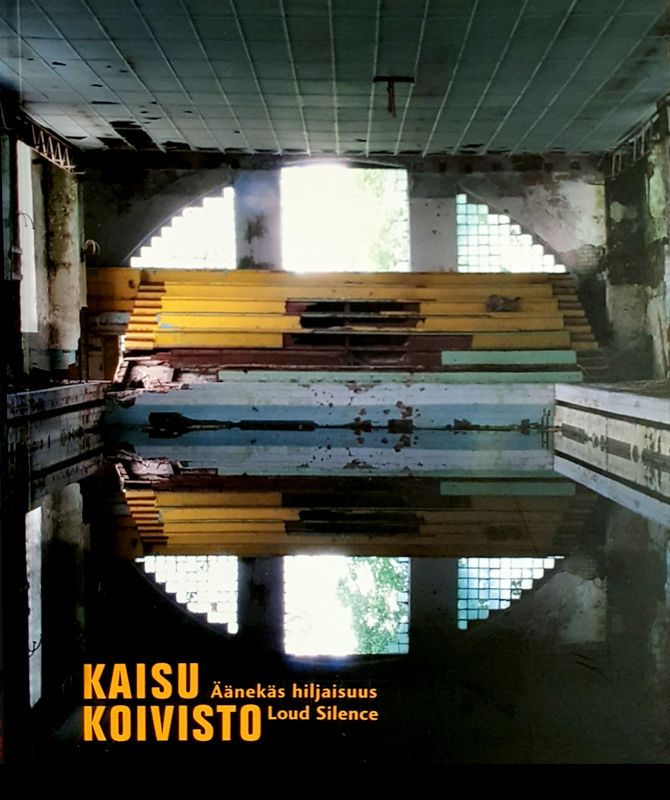

Unnatural and Inhuman Touch

By Taru Elfving

Published in Kaisu Koivisto’s monography Kaisu Koivisto Äänekäs Hiljaisuus – Loud Silence (Aboa Vetus & Ars Nova, The Matti Koivurinta Foundation, Turku 2012)

“all that is unhuman is not un-kind” (Donna Haraway) [i]

I stare into the eyes of a puppy. All round head and huge eyes, the puppy is out of proportion and unable to return my gaze. Its air of sadness, as if it was begging for affection, may actually emanate from me. The austerity of glass and steel disallows contact. Looking into this mirror I cannot recognize myself.

Diving into a psychedelic sea of glass flowers in the puppy’s eyes is to enter into nature reduced to an image and packaged for consumption. In other recent works by Kaisu Koivisto cow horns terrify as frankensteinian teeth while fishhooks are waiting to loop around someone’s neck. Is it nature threatening us here or frenzied attempts to govern nature? Mortality haunts, like the skin of a polar bear, with inevitable change that we can influence yet never fully determine. Koivisto explores in her art the anxieties projected onto nature and the materiality excluded from the human realm. Horns, teeth and hair horrify when detached from life. Similarly fur and leather, when dislodged from their ordinary functions, give us sudden shivers as echoes of death – as excess, waste, decay. But the swans and bambies dressed in neat slinky leather suits do not keep within safe bounds either. The fairy tale animals reveal another side of femininity, sexuality and embodiment in all its repressed glory. There is a thin line between lovely and ugly.

The wild other sex, culture, religion, nature can be viewed from a safe distance in a leather helmet provided by Koivisto. Like an astronaut or a diver in an alien and dangerous world. Hidden from the view of others, assuming invisibility, as the centre and boundaries of one’s own reality. Zero contact, no risk of contamination. Alone. What can I see from within the helmet? Should I step in or surrender to its gaze? The stare of Xenophobia is oppressive yet simultaneously mournful and somehow homespun. In the end I feel like stroking it. It surely just yearns for tenderness. Here lies its danger as well as its weakness, like in the populism that proudly bears it.

Alone also are the mushrooms, Changelings, which are no longer rhizomatic but rise up as isolated hollow cages. No longer nests for spores (sporangiums), they have become three-dimensional diagrams and lost their life-generating networks. On the other hand, however, they have come to resemble dishes and satellites, mirroring the work Star City. Technological innovations and systems do not so much stifle rhizomes but reproduce them: the current world order is increasingly without a centre and is ceaselessly renewed through a complex web of myriad connections that resist capture and definition. The appropriation of nature has all kinds of unexpected effects.

Organizing reality is an endless task. Structures, signs and their logic usually change shape gradually, yet at times they transform abruptly. Archives become ever more ambiguous over time. The wavering balance between control and chaos characterizes the European ideology of the nation state inscribed in the found index cards as much as the drawings added onto them. Could other living creatures be given nationality and the accompanying rights too? Borders on the world map might then be redrawn, or perhaps they would disappear altogether, like in The Nationality of Animals. With the opposition of culture and nature many other conflicts disintegrate too. The disquieting allure of the work may not be rooted in the material of malodorous and decaying fur but in the trembling of the order faltering of the structure it represents.

Koivisto adds and excavates sediments, recycles and revolves meanings, forms and materials. All sorts of persistent inconsistentenciest make their presence felt at the thresholds between the subjective and the collective, the private and the public, the past and the present. In the photographs Cows in NYC: Reintroducing the Species old plaid blankets stage a peaceful occupation of urban scenes. Silently they echo the ghostly polar bear. They are run-over. Cows no longer have a place in the cities or around them as all the space is built up and developed to its full capacity. Who can now be at home in the public space any more than in nature? Who are the homeless today?

The cow quilts make me smile at first. Their gentle melancholy resonates with the odd cuteness of the puppies. Breeding of nature for our own purposes appears strange. Cattle have been replaced by pets in the everyday of city dwellers. Do pets simply reflect their owners and respond to their needs, or are there some other modes of interaction and transformation at play – becoming animal, not only human? Can here be found a seed of empathy, of compassion, which according to the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy “is the contagion, the contact of being with one another in this turmoil. Compassion is not altruism, nor is it identification; it is the disturbance of violent relatedness.”[ii]

The coexistence of humans and animals has deep roots. Or, perhaps it is like a rhizome rather than following deterministic progressive efficiency. A possible community not founded on kinship, blood relations, and such normative ties – but on friendship, work, shared goals, grief, mortality, hope.[iii] Unnatural? Then again, not everything un-human is un-kind, as Donna Haraway reminds us.[iv] She writes about “companion species”[v] and argues that the differences and similarities between humans and animals cannot be defined through oppositions.

The approachable humour and warmth of Koivisto’s works communicate this too: more is at stake here than unnatural or humanized nature. The warps that haunt our relationship to nature are opened up for reconsideration. We need to face not only the domesticated alien and the enchanting wildness in the works, but also the fears and desires that crystallize in our encounters with them. Can there be a future without an experience of connectedness, of sharing, that allows for difference? Only then we may be touched and moved by our affinities. I just caught a glimpse of something other than my own worn image in the eyes of the puppy.

[i] Donna Haraway. Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium.FemaleMan©Meets_OncoMouse™: Feminism and Technoscience, New York: Routledge, 1997, 8.

[ii] Jean-Luc Nancy. Being Singular Plural. Stanford California: Stanford University Press, 2000, xiii.

[iii] Haraway 1997, 265.

[iv] Haraway 1997, 8.

[v] Donna Haraway. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness, Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.